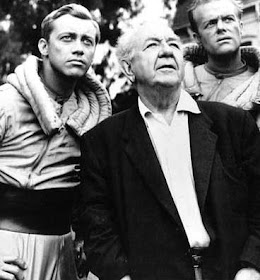

Edmund Lincoln "Eddie" Anderson (September 18, 1905 – February 28, 1977), also known as Eddie "Rochester" Anderson, was an American comedian and actor.

Anderson got his start in show business as a teenager on the vaudeville circuit. In the early 1930s, he transitioned into films and radio. In 1937, he began his most famous role of Rochester van Jones, usually known simply as "Rochester," the valet of Jack Benny, on his radio show The Jack Benny Program. Anderson became the first African American to have a regular role on a nationwide radio program. When the series moved to television, Anderson continued in the role until the series' end in 1965.

After the series ended, Anderson remained active with guest starring roles on television and voice work in animated series. He was also an avid horse-racing fan who owned several race horses and worked as a horse trainer at the Hollywood Park Racetrack.

Anderson was married twice and had four children. He died of heart disease in February 1977 at the age of 71.

Death

Anderson died of heart disease on February 28, 1977 at the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital in Woodland Hills, California. He was buried in Los Angeles in historic Evergreen Cemetery, the oldest existing cemetery in the city.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)