Eric Lynn Wright[5][6][7] (September 7, 1964 – March 26, 1995), known professionally as Eazy-E, was an American rapper, record producer, and entrepreneur. Dubbed the "Godfather of Gangsta Rap," he gained prominence for his work with N.W.A, where he has been credited for pushing the boundaries of lyrical and visual content in mainstream popular music.

Born and raised in Compton, Eazy-E faced several legal troubles before founding the Ruthless Records record label in 1986. After beginning a short solo career, where he worked heavily with Ice Cube and Dr. Dre, the trio came together to form the group N.W.A later that year. As a member of the group, he released the controversial album, Straight Outta Compton (1988), which tackled many socio-political issues. The album has been regarded as one of the greatest albums of all-time, and one of the most influential in the genre. The group released their final studio album three years later, and disbanded shortly after, due to long-standing financial disputes.

Eazy-E then resumed his solo career, where he released two EPs, which drew inspiration from funk music, contemporary hip-hop, and comedians.[8] He also engaged in a high-profile feud with Dr. Dre, before being hospitalized with AIDS in 1995. He died a month after his hospitalization.

Early life and Ruthless Records investment

Eric Wright was born to Richard and Kathie Wright on September 7, 1964, in Compton, California, a Los Angeles suburb notorious for gang activity and crime.[9][10] His father was a postal worker and his mother was a grade school administrator.[11] Wright dropped out of high school in the tenth grade,[12] but later received a high-school general equivalency diploma (GED).[13]

No one survived on the streets without a protective mask. No one survived naked. You had to have a role. You had to be "thug," "playa," "athlete," "gangsta," or "dope man." Otherwise, there was only one role left to you: "victim."

-- Jerry Heller on Eazy-E[14]

Wright supported himself primarily by selling drugs, introduced to the occupation by his cousin.[12] Wright's friend Jerry Heller admits that he witnessed Wright selling marijuana, but says that he never saw him sell cocaine. As Heller noted in his book Ruthless: A Memoir, Wright's "dope dealer" label was part of his "self-forged armor."[14] Wright was also labeled as a "thug." Heller explains: "The hood where he grew up was a dangerous place. He was a small guy. 'Thug' was a role that was widely understood on the street; it gave you a certain level of protection in the sense that people hesitated to fuck with you. Likewise, 'dope dealer' was a role that accorded you certain privileges and respect."[14]

In 1986, at the age of 22, Wright had allegedly earned as much as US$250,000 from dealing drugs. However, after his cousin was shot and killed, he decided that he could make a better living in the Los Angeles hip hop scene, which was growing rapidly in popularity.[15] He started recording songs during the mid-1980s in his parents' garage.[13]

The original idea for Ruthless Records came when Wright asked Heller to go into business with him. Wright suggested a half-ownership company, but it was later decided that Wright would get eighty percent of the company's income and Heller would only get twenty percent. According to Heller, he told Wright, "Every dollar comes into Ruthless, I take twenty cents. That's industry standard for a manager of my caliber. I take twenty, you take eighty percent. I am responsible for my expenses and you're responsible for yours. You own the company. I work for you."[14] Along with Heller, Wright invested much of his money into Ruthless Records.[16] Heller claims that he invested the first $250,000 and would eventually put up to $1,000,000 into the company.[14]

Musical career

N.W.A and Eazy-Duz-It (1986–91)

Eazy-E co-headlined Public Enemy's 1988 "Bring the Noise" concert tour along with N.W.A

N.W.A's original lineup consisted of Arabian Prince, Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, and Ice Cube.[17][18] DJ Yella and MC Ren joined later.[19] The compilation album N.W.A. and the Posse was released on November 6, 1987, and would go on to be certified Gold in the United States.[20][21] The album featured material previously released as singles on the Macola Records label, which was responsible for distributing the releases by N.W.A and other artists like the Fila Fresh Crew, a West Coast rap group originally based in Dallas, Texas.[22][23]

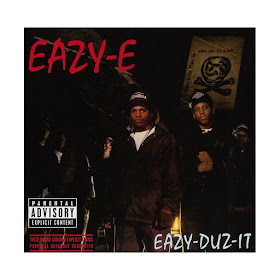

Eazy-E's debut album, Eazy-Duz-It, was released on September 16, 1988, and featured twelve tracks. It was labeled as West Coast hip hop, Gangsta rap and Golden age hip hop. It has sold over 2.5 million copies in the United States and reached number forty-one on the Billboard 200.[13][24] The album was produced by Dr. Dre and DJ Yella and largely written by MC Ren, Ice Cube and The D.O.C..[25] Both Glen Boyd from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and MTV's Jon Wiederhorn claimed that Eazy-Duz-It "paved the way" for N.W.A's most controversial album, Straight Outta Compton.[26][27] Wright's only solo in the album was a remix of the song "8 Ball," which originally appeared on N.W.A. and the Posse. The album featured Wright's writing and performing; he performed on seven songs and helped write four songs.[28]

After the release of Straight Outta Compton, Ice Cube left because of internal disputes and the group continued as a four-piece ensemble.[19] N.W.A released 100 Miles and Runnin' and Niggaz4Life in 1991. A diss war started between N.W.A and Ice Cube when "100 Miles and Runnin'" and "Real Niggaz" were released. Ice Cube responded with "No Vaseline" on Death Certificate.[29] Wright performed on seven of the eighteen songs on Niggaz4Life.[30] In March 1991 Wright accepted an invitation to a lunch benefiting the Republican Senatorial Inner Circle, hosted by then-U.S. President George H. W. Bush.[31] A spokesman for the rapper said that Eazy-E supported Bush because of his performance in the Persian Gulf War.[32]

End of N.W.A and feud with Dr. Dre (1991–94)

N.W.A began to split up after Jerry Heller became the band's manager. Dr. Dre recalls: "The split came when Jerry Heller got involved. He played the divide and conquer game. Instead of taking care of everybody, he picked one nigga to take care of and that was Eazy. And Eazy was like, 'I'm taken care of, so fuck it.'" Dre sent Suge Knight to look into Eazy's financial situation because he was beginning to grow suspicious of Eazy and Heller. Dre asked Eazy to release him from the Ruthless Records contract, but Eazy refused. The impasse led to what reportedly transpired between Knight and Eazy at the recording studio where Niggaz4life was recorded. After he refused to release Dre, Knight declared to Eazy that he had kidnapped Heller and was holding him prisoner in a van. The rumor did not convince Eazy to release Dre from his contract, and Knight threatened Eazy's family: Knight gave Eazy a piece of paper that contained Eazy's mother's address, telling him, "I know where your mama stays." Eazy finally signed Dre's release, officially ending N.W.A.[33]

The feud with Dr. Dre continued after a track on Dre's debut album The Chronic, "Fuck wit Dre Day (And Everybody's Celebratin')," contained lyrics that insulted Eazy-E. Eazy responded with the EP, It's On (Dr. Dre) 187um Killa, featuring the tracks "Real Muthaphuckkin G's" and "It's On." The album, which was released on October 25, 1993, contains pictures of Dre wearing "lacy outfits and makeup" when he was a member of the Electro-hop World Class Wreckin' Cru.[33]

Personal life

Wright had a son, Eric Darnell Wright, in 1984. He also had a daughter named Erin[34] who has legally changed her name to Ebie[35] (Ebie is currently crowd-funding a film called Ruthless Scandal: No More Lies to investigate her father's death).[36] Wright also has five other children by five separate women during his life.

Wright met Tomica Woods at a Los Angeles nightclub in 1991 and they married in 1995, twelve days before his death.[37] They had a son named Dominick and a daughter named Daijah (born six months after Wright's death).[38] After Wright's death, Ruthless Records was taken over by his wife.

Legal issues

After Dr. Dre left Ruthless Records, executives Mike Klein and Jerry Heller sought assistance from the Jewish Defense League (JDL). Klein, a former Ruthless Records director of business affairs, said this provided Ruthless Records with leverage to enter into negotiations with Death Row Records over Dr. Dre's departure.[39] While Knight had sought an outright release from Ruthless Records for Dr. Dre, the JDL and Ruthless Records management negotiated a release in which the record label would continue to receive money and publishing rights from future Dr. Dre projects with Death Row Records, founded by Dr. Dre with Suge Knight.[40] The FBI launched a money-laundering investigation under the assumption that the JDL was extorting money from Ruthless Records to fight their causes. This led to JDL spokesperson Irv Rubin issuing a press release stating "there was nothing but a close, tight relationship" between Eazy-E and the organization.[39] An FBI inquiry began in 1996 and was closed in 1999 with a finding that the allegations could not be substantiated.[41] The declassified FBI file was released to the public on the FBI's website "The Vault," part of the FOIA Library.[42]

Illness and death

Now, I'm in the biggest fight of my life and it ain't easy. But I want to say much love to those who have been down with me and thanks for all your support. Just remember: It's your real time and your real life.

--Statement from Eazy-E's camp on his behalf, March 16.[43]

On February 24, 1995, Wright was admitted to the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles with a violent cough.[44] He was diagnosed with AIDS.[45] He announced his illness in a public statement on March 16, 1995. It is believed Wright contracted the infection from a sexual partner.[15][46][47] During the week of March 20, having already made amends with Ice Cube, he drafted a final message to his fans.[48]

On March 26, 1995, Eazy-E died from complications of AIDS, one month after his diagnosis. He was 30 years old (most reports at the time said he was 31 due to the falsification of his date of birth by one year).[13][49] He was buried on April 7, 1995 at Rose Hills Memorial Park in Whittier, California.[50] Over 3,000 people attended his funeral,[51] including Jerry Heller and DJ Yella.[52][53] He was buried in a gold casket, and instead of wearing a suit and tie, Eazy-E was dressed in a flannel shirt, a Compton hat and jeans.[54] On January 30, 1996, ten months after Eazy-E's death, his final album, Str8 off tha Streetz of Muthaphukkin Compton was released.

According to his son Lil Eazy-E, Eazy-E was worth an estimated USD$50 million at the time of his death.[55]

Musical influences and style

Allmusic cites Eazy-E's influences as Ice-T, Redd Foxx, Tupac Shakur, King Tee, Bootsy Collins, Run–D.M.C., Richard Pryor, Egyptian Lover, Schoolly D, Too $hort, Prince, the Sugarhill Gang and George Clinton.[56] In the documentary The Life and Timez of Eric Wright, Eazy-E mentions collaborating with many of his influences.[57]

When reviewing Str8 off tha Streetz of Muthaphukkin Compton, Stephen Thomas Erlewine noted "... Eazy-E sounds revitalized, but the music simply isn't imaginative. Instead of pushing forward and creating a distinctive style, it treads over familiar gangsta territory, complete with bottomless bass, whining synthesizers, and meaningless boasts."[58] When reviewing Eazy-Duz-It, Jason Birchmeier of Allmusic said, "In terms of production, Dr. Dre and Yella meld together P-Funk, Def Jam-style hip-hop and the leftover electro sounds of mid-'80s Los Angeles, creating a dense, funky, and thoroughly unique style of their own." Birchmeier described Eazy's style as "dense, unique and funky," and said that it sounded "absolutely revolutionary in 1988."[56]

Several members of N.W.A wrote lyrics for Eazy-Duz-It: Ice Cube, The D.O.C. and MC Ren.[59] The EP 5150: Home 4 tha Sick features a song written by Naughty By Nature. The track "Merry Muthaphuckkin' Xmas" features Menajahtwa, Buckwheat, and Atban Klann as guest vocalists, and "Neighborhood Sniper" features Kokane as a guest vocalist.[60] It's On (Dr. Dre) 187um Killa features several guest vocalists, including Gangsta Dresta, B.G. Knocc Out. Kokane, Cold 187um, Rhythum D, and Dirty Red.[61] Str8 off tha Streetz of Muthaphukkin Compton featured several guest vocalists, including B.G. Knocc Out, Gangsta Dresta, Sylk-E. Fyne, Dirty Red, Menajahtwa, Roger Troutman and ex-N.W.A members MC Ren and DJ Yella.[62]

Legacy

Eazy-E has been called the godfather of gangsta rap[63][64][65][66] MTV's Reid Shaheem said that Eazy was a "rap-pioneer,"[66] and he is sometimes cited by critics as a legend.[67][68] Steve Huey of AllMusic said that he was "one of the most controversial figures in gangsta rap."[8] Since his 1995 death, many book and video biographies have been produced, including 2002's The Day Eazy-E Died and Dead and Gone.[69][70][71]

When Eazy was diagnosed with AIDS, many magazines like Jet,[72] Vibe,[73] Billboard,[74] The Crisis,[75] and Newsweek covered the story and released information on the topic.[76] All of his studio albums and EPs charted on the Billboard 200,[77][78][79] and many of his singles—"Eazy-Duz-It," "We Want Eazy," "Real Muthaphuckkin G's," and "Just tah Let U Know"—also charted in the U.S.[79][80]

In 2012 a Eazy-E documentary was released by Ruthless Propaganda, called Ruthless Memories. The documentary featured interviews from Jerry Heller, MC Ren and B.G. Knocc Out.[81]

In the 2015 film Straight Outta Compton, Eazy-E is played by Jason Mitchell and the film is dedicated in his memory.[82]

Discography

Studio albums

Eazy-Duz-It (1988)

Str8 off tha Streetz of Muthaphukkin Compton (1996)

Extended Plays

5150: Home 4 tha Sick (1992)

It's On (Dr. Dre) 187um Killa (1993)

Impact of a Legend (2002)

with N.W.A

N.W.A. and the Posse (1987)

Straight Outta Compton (1988)

Niggaz4Life (1991)

References

1."Eric L Wright, Born 09/07/1964 in California". California Birth Index.

2. Rani, Taj; Reagans, Dan (September 7, 2014). "Happy 50th Birthday, Eazy-E". BET. ...he's making fifty this year. He was born on the September the seven, nineteen sixty-four [sic]

3. Westhoff, Ben (2017). Original Gangstas: The Untold Story of Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, Ice Cube, Tupac Shakur, and the Birth of West Coast Rap. New York: Hachette Books. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-3163-4485-2. Though Eazy's gravestone, and most obituaries, list his birth year as 1963, that is likely not accurate. The funeral program gave his birth year as 1964, as do most official court documents. That would make him only thirty at his death, rather than thirty-one as was widely reported.

4. djvlad (5 February 2016). Lil Eazy-E Tears Up as He Recalls Final Moments with Father Before His Death (YouTube). Event occurs at second 23.

5. "Top Five Most Wanted". Billboard: 38. August 9, 2008.

6. Miller, Michael (2008). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Music History. Alpha. p. 219. ISBN 1-59257-751-2.

7. "Celebrities We've Lost To AIDS | Lifestyle|BET.com" Archived February 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Bet.com. November 19, 2007

8. Huey, Steve (2003). "Eazy-E Biography". Allmusic. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

9. Hochman, Steve (March 28, 1995). "Rap Star, Record Company Founder Eazy-E Dies of AIDS". Los Angeles Times.

10. "Hip-Hop News: Remembering Eric 'Eazy-E' Wright". Rap News Network. March 26, 2006

11. Harris, Carter (June–July 1995). "Eazy Living". Vibe. 3 (5): 62.

12. "Straight Outta Left Field". Dallas Observer. September 12, 2002.

13. Pareles, Jon (March 28, 1995). "Eazy-E, 31, Performer Who Put Gangster Rap on the Charts". The New York Times.

14. Heller, Jerry (2007). Ruthless: A Memoir. Gallery. pp. 65–77. ISBN 978-1-4169-1794-6.

15. Chang, Jeff (April 24, 2004). "The Last Days of Eazy E". Swindle. Archived from the original on October 25, 2007. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

16. Hunt, Dennis (October 22, 1989). "Dr. Dre Joins an Illustrious Pack In the last year, producer has hit with albums for N.W.A, Eazy-E, J. J. Fad and the D.O.C.". Los Angeles Times.

17. "Arabian Prince interview". www.huffingtonpost.com. Huffington Post. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

18. "Arabian Prince interview". www.vladtv.com. VladTV. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

19. Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2000). "N.W.A. – Biography". Allmusic.

20. Koroma, Salima (September 29, 2008) "Vh1 Airs Documentary On N.W.A.". Hiphopdx.com.

21. "Gold and Platinum – November 26, 2010". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

22. Bynoe, Yvonne (2005). Encyclopedia of Rap and Hip Hop Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 294. ISBN 0-313-33058-1.

23. Brackett, Nathan (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide: Completely Revised and Updated 4th Edition. Fireside Books. p. 248. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

24. "Eazy-Duz-It – Eazy-E". Billboard. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

25. Eazy-Duz-It (Media notes). Eazy-E. Ruthless, Priority. 1988.

26. Boyd, Glen (March 20, 2010). "Music Review: Eazy E - Eazy Duz It (Uncut Snoop Dogg Approved Edition/Remastered)". Seattle Post-Intelligencer

27. Wiederhorn, Jon. (July 31, 2002). "N.W.A Classics To Be Reissued With Bonus Tracks". MTV.

28. Straight Outta Compton (Media notes). N.W.A. Ruthless/Priority/EMI Records. 1988.

29. Lazerine, Cameron; Lazerine, Devin (2008). Rap-Up: The Ultimate Guide to Hip-Hop and R and B. Grand Central Publications. pp. 43–67. ISBN 978-0-446-17820-4.

30. Niggaz4Life (Media notes). N.W.A. Ruthless/Priority. 1991.

31. "Rap's Bad Boy to Get Lunch With the Prez". Los Angeles Times. March 18, 1991.

32. "Do the Right-Wing Thing". Entertainment Weekly (59). March 29, 1991.

33. Borgmeyer, Jon; Lang, Holly (2006). Dr. Dre: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 52–55. ISBN 0-313-33826-4.

34. "Eazy-E's daughter pays photo tribute, says father due more respect"

35. "A lot of people remember "Erin" from TV but my family has called me "E.B." (my initials) since birth."

36. Bandini (October 19, 2016). "Eazy E's daughter tries to crowd-fund to investigate father's death". ambrosiaforheads.

37. "Woods-Wright, Tomica"

38. "6 Months After Aids Kills Rapper, His Baby Is Born" .

39. Berry, Jahna (September 19, 2000). "The FBI Screws Up Again". Jewish Defense League. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009.

40. Moss, Corey (July 18, 2003). "50 Cent, Eminem, Dr. Dre Face Suge Knight At 'Da Club': VMA Lens Recap". MTV.

41. Rosenzweig, David (November 2, 2002). "JDL Leader's Attorneys Seek FBI Inquiry Files". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035.

42. "Eric Wright (Eazy-E, EZ E) Part 01 of 01". FBI.

43. Westhoff 2017, pp. 278–279.

44. Staff (4 September 1995). "A Gangster Wake-Up Call". Newsweek.

"Rapper Eazy E hospitalized with AIDS". UPI. Los Angeles. 17 March 1995.

46. Borgmeyer, Jon; Lang, Holly (2006). Dr. Dre: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0-313-33826-4.

47. Talia, Pele (September 1995). "Vibe article". Vibe. 3 (7): 32.

48. "Eazy-E's Last Words".

49. Kapsambelis, Niki (March 27, 1995). "Gangsta rapper Eazy-E dies of AIDS". Park City Daily News. p. 39.

50. "Rose Hills Memorial Park, Whittier, CA". Notable Names Database.

51. Williams, Frank B. (8 April 1995). "Thousands Flock to Funeral for Eazy-E : Music: Overflow crowd is drawn to 'gangsta' rap star's service. Eulogy notes his contributions but warns of danger of AIDS, which killed the rapper". Los Angeles Times.

52. Mixon, Jon (7 October 2016). "Why didn't Dr. Dre, Ice Cube or MC Ren attend Eazy-E's funeral?". Quora.

53. Schwartz, Danny (8 September 2015). "DJ Yella Says He Was The Only Member Of N.W.A. To Attend Eazy-E's Funeral". HotNewHipHop.

54. "10 Most Interesting Facts About Eazy-E You May Not Know".

55. "Lil Eazy-E: My Father Was Worth $50 Million When He Passed Away". YouTube.

56. Huey, Steve. "Eazy-E". Allmusic.

57. The Life and Timez of Eric Wright (Color, DVD, NTSC)|format= requires |url= (help). April 2, 2002. Event occurs at 21:03. ASIN B000063UQQ.

58. Thomas, Stephen. "Str8 Off tha Streetz of Muthaphu**in Compton – Eazy-E". Allmusic. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

59. Eazy-Duz-It (CD). Eazy-E. Ruthless, Priority. 1988.

60. 5150: Home 4 tha Sick (CD). Eazy-E. Ruthless, Priority. 1992.

61. It's On (Dr. Dre) 187um Killa (CD). Eazy-E. Ruthless/Relativity/Epic. 1993.

62. Str8 off tha Streetz of Muthaphukkin Compton (CD). Eazy-E. Ruthless, Relativity, Epic. 1995.

63. Simmonds, Jeremy (2008). The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars: Heroin, Handguns, and Ham Sandwiches. Chicago Review Press. p. 332. ISBN 1-55652-754-3.

64. "Widow of Rapper Eazy-E Gives Birth To Child". Jet. 88 (23): 40. October 16, 1995.

65. The Black Dot (2005). Hip Hop Decoded: From Its Ancient Origin to Its Modern Day Matrix. MOME Publishing. p. 100. ISBN 0-9772357-0-X.

66. Shaheem, Reid (March 26, 2010). "Lil Eazy-E Remembers His Dad, 15 Years Later". MTV.

67. Davis, Todd. "Lil Eazy-E: Son of a Legend". Hiphopdx.com. December 9, 2005.

68. "About the Official Hip Hop Hall Of Fame and Producer JT Thompson". Live-PR.com. November 16, 2010.

69. "The Day Eazy-E Died (A B-Boy Blues Novel #4) (9781555837600): James Earl Hardy: Books". Amazon.com. ISBN 1555837603. Missing or empty |url= (help)

70. "Day Eazy E Died [PB,2002]: Jema Eerl Herdy: Books". Amazon.com. September 9, 2009.

71. "Dead and Gone: Tupac, Eazy-E, Notorias BIG, Aaliyah, Big Pun, Big L: Video". Amazon.com. September 9, 2009.

72. "Rap Star Eazy-E Battles AIDS; Listed in Critical Condition in LA Hospital". Jet: 13. April 3, 2010.

73. "The Invisible Woman". Vibe: 62. June–July 1995.

74. HN (August 9, 1997). "Ruthless Sounds". Billboard: 44.

75. Colin, Potter (July 1995). "AIDS in Black America: It's Not Just A Gay Thing". The Crisis: 34–35.

76. Smith, Rex. "Newsweek article". Newsweek. 137 (10–18): 609.

77. "Eazy-E". Allmusic.

78. "Eazy-E". Allmusic.

79. "Eazy-E". Allmusic.

80. "Eazy-E". Allmusic.

81. "Eazy-E Documentary To Release, Featuring Jerry Heller, MC Ren, B.G. Knocc Out".

82. "Jason Mitchell". IMDB. 2015.

Literature

Westhoff, Ben (2017). Original Gangstas: The Untold Story of Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, Ice Cube, Tupac Shakur, and the Birth of West Coast Rap. New York: Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0-3163-4485-2.