Friday, May 29, 2020

"The Dark Country" Fantasy/Horror Author Dennis Etchison 2019 Westwood Village Cemetery

Dennis William Etchison (March 30, 1943 – May 29, 2019) was an American writer and editor of fantasy and horror fiction. [1] Etchison referred to his own work as "rather dark, depressing, almost pathologically inward fiction about the individual in relation to the world." Stephen King has called Dennis Etchison "one hell of a fiction writer" and he has been called "the most original living horror writer in America" (The Viking-Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural).[2]

While he has achieved some acclaim as a novelist, it is Etchison's work in the short story format that is especially well-regarded by critics and genre fans, as with his debut collection The Dark Country (1982) selected as one of the 100 best horror books.[3] He was President of the Horror Writers Association from 1992 to 1994. He was a multi-award winner, having won the British Fantasy Award three times for fiction, and the World Fantasy Award for anthologies he edited.

Early years

Etchison was born in Stockton, California. An only child, the earliest years of his life were spent growing up in a household devoid of men (World War II was still raging across the globe). Etchison has remarked that he was greatly spoiled during his early years and largely isolated from other children. This sense of isolation and need to interact with society would later form the themes to many of his works.[2]

In his early years, Etchison also became an avid wrestling fan. Fascinated by the interplay between good and evil, he would regularly attend shows at the Olympic Auditorium with his father. His passion for the sport continues to this day, and he often writes under the pen name "The Pro" for the wrestling publication Rampage.

In junior high and high school, Etchison wrote for the school paper and won numerous essay contests. He discovered Ray Bradbury during this time and emulated him before developing his own style. On the last day of his junior year in high school, Etchison began writing his first short story. Entitled "Odd Boy Out," it involved a group of teenagers in the woods. He began submitting it to numerous science-fiction magazines but received rejection slips each time.

He then remembered Ray Bradbury once suggesting that a writer should start by submitting their work to the least likely market. So he submitted his short story to a gentlemen's magazine called Escapade, and, a few weeks later, he received their acceptance and a check for $125.

Film studies and screen work

Etchison has written professionally in many genres since 1960. He attended UCLA film school in the 1960s and has written many screenplays as yet unproduced, from his own works as well as those of Ray Bradbury ("The Fox and the Forest") and Stephen King ("The Mist"). He rewrote a Colin Wilson script, The Ogre, and completed a screenplay based on his own short story "The Late Shift." He co-wrote a story for the Logan's Run TV series, "The Thunder Gods" (printed in The Circuit 2, No 3).

In 1983, Etchison was asked by Stephen King to be the film consultant/historian on King's book on the horror genre, Danse Macabre.

In 1984, ZBS Media produced a 90-minute radio version of Stephen King's The Mist, based on Etchison's script. A film, "Killing Time," was made by Patrick Aumont and Damian Harris (Graymatter Productions) from Etchison's story "The Late Shift."[2]

In 1985, Etchison served as staff writer for the HBO TV series The Hitchhiker.

In 1986, John Carpenter teamed up with Etchison to write a script to Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers.[4]

"Halloween was banned in Haddonfield and I think that the basic idea was that if you tried to suppress something, it would only rear its head more strongly. By the very [attempt] of trying to erase the memory of Michael Myers, [the teenagers] were going to ironically bring him back into existence."

— Dennis Etchison on his idea for Halloween 4.[5]

However, franchise producer Moustapha Akkad rejected the Etchison script, calling it "too cerebral" and insisting that any new Halloween sequel must feature Myers as a flesh and blood killer.[6] In an interview, Etchison explained how he received the phone call informing him of the rejection of his script. Etchison said, "I received a call from Debra Hill and she said, 'Dennis, I just wanted you to know that John and I have sold our interest in the title 'Halloween' and unfortunately, your script was not part of the deal."[5]

Carpenter and Hill had signed all of their rights away to Akkad, who gained ownership. Akkad says, "I just went back to the basics of Halloween on Halloween 4 and it was the most successful."[7] As Carpenter refused to continue his involvement with the series, a new director was sought out. Dwight H. Little, a native of Ohio, replaced Carpenter.

Fiction writing

Etchison's fiction has appeared regularly since 1961 in a wide range of publications including Cavalier, The Oneota Review, Rogue, Seventeen, Statement, Fantastic Stories, Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Mystery Monthly, Escapade, Adelina, Comet (Germany), Fiction (France), Universe (France), Fantasy Tales, Weirdbook, Whispers, Fantasy Book and in such anthologies as Orbit, New Writings in SF, Rod Serling's Other Worlds, Prize Stories from Seventeen, The Pseudo-People, and The Future is Now.[2] His stories can also be found in many of the major horror and dark fantasy anthologies including Frights, Dark Forces, Terrors, New Terrors, Horrors, Fears, Nightmares, Shadows, Whispers, Night Chills, Death, World Fantasy Awards, Mad Scientists, Year's Best Horror Stories, The Dodd, Mead Gallery of Horror, Midnight and others.[2]

His first short story collection, The Dark Country, was published in 1982. Its title story received the World Fantasy Award[8] (tied with Stephen King), as well as the British Fantasy Award[9] for Best Collection of that year – the first time one writer received both major awards for a single work.

Etchison nearly had his first short story collection appear eleven years earlier. In 1971 he sold Powell Books, a low-budget Los Angeles based publisher who published Karl Edward Wagner's Darkness Weaves, a collection of his science fiction and fantasy under the title The Night of the Eye. The book went into galley proofs and beyond – Etchison received a cover proof, and ISBN 0-8427-1014-0 was assigned. On the eve of its publication, Powell Publications went bankrupt. Etchison would wait over a decade before his actual first collection The Dark Country would appear, to critical acclaim.

Several more collections have been published since, including a career retrospective, Talking in the Dark (2001), which consists of stories personally selected by the author. He was nominated for the British Fantasy Award for "The Late Shift" (1981), and as well as winning the ward in 1982 for "The Dark Country," has won it since for Best Short Story, for "The Olympic Runner" (1986) and "The Dog Park" (1994).[9]

Etchison's first novel (discounting two pseudonymous erotic novels), The Shudder, was slated for publication in 1980; he finally withdrew it when the editor demanded what he felt were unreasonable changes in the manuscript. A portion of the novel appeared as one selection in A Fantasy Reader, the book of the Seventh World Fantasy Convention in 1981; the full novel remains unpublished.

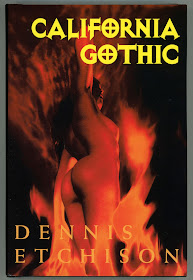

Writing under the pseudonym of "Jack Martin," he published popular novelizations of the films Halloween II (1981), Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), and Videodrome (1983). Under his own name, Etchison's novels include Darkside (1986), Shadowman (1993), and California Gothic (1995), as well as the novelization of John Carpenter's The Fog (1980).

Etchison periodically taught classes in creative writing at UCLA.[2]

Editorial work

As editor, Etchison has received two World Fantasy Awards for Best Anthology, for MetaHorror (1993) and The Museum of Horrors (2002). His other anthologies include the critically acclaimed Cutting Edge (1986), Gathering The Bones (2003) (edited with Ramsey Campbell and Jack Dann), and the Masters of Darkness series (three volumes).

Radio work

In 2002, Etchison adapted nearly 100 episodes of the original Twilight Zone TV series for a CBS radio series hosted by Stacy Keach. The programmes were commercially released on audio CDs. Etchison was one of the writers on the audio series Fangoria's Dreadtime Stories hosted by Malcolm McDowell. These horrific stories are available on CD and via digital download at iTunes, Audible and through other outlets.

Essays and other works

The Book of Lists: Horror – 2008 (contributor)

Etchison contributed a Foreword to George Clayton Johnson's All of Us Are Dying and Other Stories (Subterranean Press, 1999).

Death

A message posted to Etchison's Facebook page reported that the author had died on May 28, 2019; no cause of death was given.[10] Locus magazine published Etchison's obituary on May 29 2019.[1] He was survived by his wife Kristina.[1]

Dennis Etchison has a memorial plaque at Westwood Village Memorial Park in Los Angeles, California.

Critical reception

The late Karl Edward Wagner proclaimed him "the finest writer of psychological horror this genre has ever produced."[11] Charles L. Grant called Etchison "the best short story writer in the field today, bar none."[12]

Critical studies of Etchison's work can be found in Darrell Schweitzer's Discovering Modern Horror Fiction,[13] Richard Bleiler's Supernatural Fiction Writers [14] and "Dennis Etchison: Spanning the Genres" in S. T. Joshi's book The Evolution of the Weird Tale (2004), 178–89.[15]

Bibliography

Novels

Stud Row (LA: Oasis Books, 1969) (written as "H.L. Mensch" by Etchison and Eric Cohen)

Loves and Intrigues of Damon (LA: Oasis Books, 1969) (written as "Ben Dover") (based in part upon an idea by Charles Beaumont)

The Shudder (Coward, McCann, Geoghegan, 1980) ISBN 0-698-10991-0. Despite Etchison receiving an advance, and the book being assigned an ISBN, the novel was not published; it was withdrawn by the author (see details above).

The Fog (1980)

Halloween II (1981) (written as "Jack Martin")

Halloween III (1982) (written as "Jack Martin")

Videodrome (1983) (written as "Jack Martin")

Darkside (1986)

Shadowman (1993)

California Gothic (1995)

Double Edge (1997)

Short story collections

The Dark Country (1982)

Red Dreams (1984)

The Blood Kiss (1987)

The Death Artist (2000)

Retrospective collections

Talking in the Dark (2001) (plus one new story, "Red Dog Down"). This volume marked the 40th anniversary of Etchison's first professional first short story sale.

Fine Cuts (e-collection, Scorpius Digital, 2006) (Hollywood-themed volume plus one previously uncollected story, "Got To Kill Them All")

Got To Kill Them All and other stories (CD Publications, 2008) (plus three previously uncollected stories, "One of Us," "In a Silent Way," and "My Present Wife," together with "Red Dog Down" and "Got To Kill Them All," previously included in prior retrospectives)

As editor

Cutting Edge (1986)

Masters of Darkness (1986)

Masters of Darkness II (1988)

Lord John Ten (1988)

Masters of Darkness III (1991)

The Complete Masters of Darkness (1991)

MetaHorror (1992). This anthology won the World Fantasy Award for Best Anthology, 1993.

The Museum of Horrors (Leisure Books, 2001). This anthology won the World Fantasy Award for Best Anthology, 2002.

Gathering The Bones (2003) (Edited with Ramsey Campbell and Jack Dann)

Other works

The Walk: A Tor.Com Original (2014)

Select awards and honors

Etchison was nominated for and also won multiple awards for his various works.[16]

Year Organization Award title,

Category Work Result Refs

1977 World Fantasy Convention World Fantasy Award,

Best Short Fiction "It Only Comes Out at Night" Nominated [17][18]

1981 British Fantasy Society British Fantasy Award,

Best Short Fiction "The Late Shift" Nominated [19]

1982 British Fantasy Society British Fantasy Award,

Best Short Story "The Dark Country" Won [20]

1982 World Fantasy Convention World Fantasy Award,

Best Short Fiction "The Dark Country" Won [21]

1983 World Fantasy Convention World Fantasy Award,

Best Short Fiction "Deathtracks" Nominated [22]

1983 World Fantasy Convention World Fantasy Award,

Best Anthology/Collection The Dark Country Nominated [22]

1987 British Fantasy Society British Fantasy Award,

Best Short Story "The Olympic Runner" Won [23]

1987 World Fantasy Convention World Fantasy Award,

Best Anthology/Collection Cutting Edge Nominated [24]

1988 Horror Writers Association Bram Stoker Award,

Superior Achievement in a Fiction Collection The Blood Kiss Nominated [25]

1989 World Fantasy Convention World Fantasy Award,

Best Collection The Blood Kiss Nominated [26]

1993 Horror Writers Association Bram Stoker Award,

Superior Achievement in Short Fiction "The Dog Park" Nominated [27]

1997 World Fantasy Convention World Fantasy Award,

Best Short Fiction "The Dead Cop" Nominated [28]

1998 International Horror Guild International Horror Guild Award,

Best Short Form "Inside the Cackle Factory" Nominated [29]

2000 International Horror Guild International Horror Guild Award,

Best Collection "The Death Artist" Nominated [30]

2001 International Horror Guild International Horror Guild Award,

Best Anthology The Museum of Horrors Nominated [31]

2001 International Horror Guild International Horror Guild Award,

Best Collection Talking in the Dark Nominated [31]

2002 World Fantasy Convention World Fantasy Award,

Best Anthology The Museum of Horrors Won [32]

2002 World Fantasy Convention World Fantasy Award,

Best Collection Talking in the Dark Nominated [32]

2003 Horror Writers Association Bram Stoker Award,

Superior Achievement in an Anthology Gathering the Bones

with Ramsey Campbell and Jack Dann Nominated [33]

2003 International Horror Guild International Horror Guild Award,

Best Anthology Gathering the Bones

with Ramsey Campbell and Jack Dann Nominated [34]

2004 World Fantasy Convention World Fantasy Award,

Best Anthology Gathering the Bones Nominated [35]

2009 Horror Writers Association Bram Stoker Award,

Superior Achievement in a Fiction Collection Got to Kill Them All and Other Stories Nominated [36]

2016 Horror Writers Association Bram Stoker Award,

Lifetime Achievement Won [37]

References

1. Dennis Etchison (Obituary) Locus Magazine, May 29, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

2. Mathew, David, "Arterial Motives: Dennis Etchison Interviewed." Interzone No. 133, July 1998 (p. 23-26).

3. Stephen Jones and Kim Newman (eds). Horror: The 100 Best Books. Running Press, 1993

4. Assip, Mike (January 6, 2017). "Exclusive Interview: Dennis Etchison On His Unmade HALLOWEEN 4 and The Ghosts Of The Lost River Drive-In." Blumhouse.com. Archived from the original on January 8, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

5. Dennis Etchison (2006). Halloween: 25 Years of Terror DVD (DVD). United States: Trancas International Pictures.

6. An AMC special "Backdraft," a show about the behind the scenes info on the whole Halloween series clarified all of this information.

7. Moustapha Akkad (2006). Halloween: 25 Years of Terror DVD (DVD). United States: Trancas International Pictures.

8. "1982 World Fantasy Award Winners and nominees". World Fantasy Convention. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2007.

9. "Past British Fantasy Society Award Winners 1972 – 2006". British Fantasy Organization. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved July 9, 2007.

10. https://www.facebook.com/officialdennisetchisonpage/posts/1405652072908887?__tn__=-R

11. Wagner, Karl Edward. "The Dark Country". Babbage Press, blurb by Wagner. Archived from the original on July 1, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

12. Grant, Charles L. "The Dark Country". Babbage Press, blurb by Grant. Archived from the original on July 1, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

13. Stamm, M. E. "Dark side of the American Dream, The: Dennis Etchison" in: Schweitzer, Darrell, ed. Discovering Modern Horror Fiction I. Mercer Island: Starmont, 1985. (pp. 48–55).ISBN 9781587150104

14. Kelleghan, Fiona "Dennis Etchison", in Bleiler, Richard, Ed. Supernatural Fiction Writers: Contemporary Fantasy and Horror. New York: Thomson/Gale, 2003. (pp. 347–354) ISBN 9780684312507

15. Joshi, S.T., The Evolution of the Weird Tale, Hippocampus, 2004. ISBN 0-9748789-2-8

16. "Award Bibliography: Dennis Etchison". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

17. "1977 World Fantasy Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

18. "World Fantasy Awards 1977". Science Fiction Awards Database. Locus Science Fiction Foundation. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

19. "1981 British Fantasy Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

20. "Award Category: Best Short Story (British Fantasy Award)". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

21. "1982 World Fantasy Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

22. "1983 World Fantasy Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

23. "1987 British Fantasy Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

24. "1987 World Fantasy Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

25. "1988 Bram Stoker Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

26. "1989 World Fantasy Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

27. "1993 Bram Stoker Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

28. "1997 World Fantasy Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

29. "1998 International Horror Guild Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

30. "2000 International Horror Guild Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

31. "2001 International Horror Guild Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

32. "2002 World Fantasy Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

33. "2003 Bram Stoker Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

34. "2003 International Horror Guild Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

35. "2004 World Fantasy Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

36. "2009 Bram Stoker Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

37. "2016 Bram Stoker Award". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

Further reading

Schweitzer, Darrell. [Interview with Dennis Etchison]. Fantasy Newsletter, 4, No 3 (March 1981).

Stamm, Michael E. "The Dark Side of the American Dream: Dennis Etchison". In Darrell Schweitzer (ed), Discovering Modern Horror Fiction, Mercer Island, WA: Starmont House, July 1985, pp. 48–55.

Wagner, Karl Edward. 'On Fantasy' column devoted to Etchsion, Fantasy Newsletter, 6, No 2 (Feb 1982).

Thursday, May 14, 2020

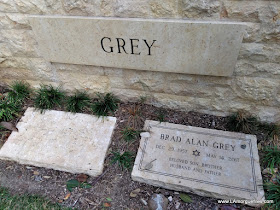

"The Sopranos" Producer Brad Grey 2017 Hillside Cemetery

Brad Alan Grey (December 29, 1957 – May 14, 2017) was an American television and film producer. He co-founded the Brillstein-Grey Entertainment agency, and afterwards became the chairman and CEO of Paramount Pictures, a position he held from 2005[1] until 2017. Grey graduated from the State University of New York at Buffalo School of Management. Under Grey's leadership, Paramount finished No. 1 in global market share in 2011 and No. 2 domestically in 2008, 2009, and 2010, despite releasing significantly fewer films than its competitors.[2][3] He also produced eight out of Paramount's 10 top-grossing pictures of all time after having succeeded Sherry Lansing in 2005.[4]

Early life

Grey was born to a Jewish family in the Bronx,[5][6][7] the youngest child of a garment district salesman. He majored in business and communications at the University at Buffalo.[8] While attending the university, he became a gofer for a young Harvey Weinstein, who was then a concert promoter. The first show Grey produced (at age 20) was a concert by Frank Sinatra at Buffalo's Buffalo Memorial Auditorium in 1978. Grey traveled to Manhattan on weekends to look for young comics at The Improv. Grey brought comedian Bob Saget to New York, thus making Saget his first client.[9]

In 1984, Grey met talent manager Bernie Brillstein in San Francisco, California at a television convention. Having convinced Brillstein that he could deliver fresh talent, he was taken on as a partner and the Bernie Brillstein Company was re-christened Brillstein-Grey Entertainment.[10] Grey began producing for television in 1986 with the Showtime hit, It's Garry Shandling's Show. In the late 1990s, Shandling sued Grey for breach of duties and related claims. Shandling complained that his TV show lost its best writers and producers when Brad Grey got them deals to do other projects, and that Grey commissioned these other deals, while Shandling did not benefit from them. Grey denied the allegations and countersued, saying the comedian breached his contract on The Larry Sanders Show by failing to produce some episodes and indiscriminately dismissing writers, among other actions.[11]

Both suits were settled avoiding a trial.[12] Shandling did testify about Grey during the 2008 trial of private investigator Anthony Pellicano who worked on Grey's defense team.[13][14] The value of the settlement to Shandling was later disputed by attorneys as being either $4 million or $10 million.[15][16]

In 1996, Brillstein sold his shares of the Brillstein-Grey company to Grey, giving Grey full rein over operations; the company's television unit was subsequently rechristened "Brad Grey Television." Grey produced shows such as Emmy Award-winning The Sopranos and The Wayne Brady Show. Other shows developed in the 1990s under the Brillstein-Grey banner included Good Sports, The Larry Sanders Show, Mr. Show, Real Time with Bill Maher, The Sopranos, NewsRadio, and Just Shoot Me! Grey also ventured into film by producing the Adam Sandler hit, Happy Gilmore.

In 1996, actress Linda Doucett alleged that Brad Grey and Garry Shandling fired her from The Larry Sanders Show after her personal relationship with Shandling ended.[17] Doucett reportedly received a $1 million settlement in this matter in 1997.

In July 2000 - on the day of Scary Movie’s opening - Grey and Brillstein-Grey were sued by Bo Zenga and his Boz Productions in what became known as the ‘Scary’ suit.[18] Zenga, at the time an unknown bit-part actor [19] “claimed he had an oral agreement with Grey’s management firm Brillstein-Grey Entertainment, giving him equal profits on the film.”[18] ‘Scary Movie’ went on to make $278m worldwide.[20]

The pre-trial discovery process "revealed that major parts of Zenga’s resume were fabricated. Brillstein-Grey said in a court filing that Zenga presented himself as a successful investment banker who became a prize-winning screenwriter to satisfy his creative urges.” [18] “Far from being a successful investment banker, Zenga once filed for personal bankruptcy” [18] and “according to court papers, the only writing award he won was in a phony contest he set up himself.” [18] After denying under oath that he knew who owned the company that ran the contest, Bo Zenga recanted a day later, admitting his ownership of the company and “saying he had been "overmedicated.”” [21] When questioned about “an accusation from his former business partner that he coerced her to lie for him” [18] Zenga “in a highly unusual move for a plaintiff in a film-profits case — asserted his Fifth Amendment right not to answer hundreds of questions.” [18] Bo Zenga's suit was thrown out of court for lack of evidence. L.A. Superior Court Judge Robert O’Brien “noted it was only the second time in all his years on the bench that he had granted a non-suit and taken a case away from a jury.” [18]

In 2002, Grey formed Plan B with Brad Pitt and Jennifer Aniston, with a first-look deal at Warner Bros. The company produced two films for Warner Bros: Tim Burton's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory with Johnny Depp, and Martin Scorsese's The Departed, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Matt Damon, and Jack Nicholson. After Pitt and Aniston separated, Grey and Pitt moved the company to Paramount Pictures in 2005.[22]

In May 2006 Bo Zenga “filed a new suit against Grey personally," [23] in which he charged Grey with using notorious private investigator Anthony Pellicano to illegally wiretap and conduct illegal background checks on Zenga during the original case. Grey denied any knowledge, testifying that "his dealings with Pellicano “all came through Bert Fields” and that “in every instance” Grey had never been given updates on the investigations by Pellicano." [24] The suit was “dismissed, due to Zenga having lied and to statute of limitations issues.“ [25] Bo Zenga's appeal continued after Grey's death, until that too was dismissed in December 2017.

On October 17, 2017, writer Janis Hirsch alleged that her response to workplace sexual harassment resulted in a meeting with Brad Grey, during which he pressured her to quit her job during the late 1980s.[26]

Paramount Pictures CEO, 2005–2017

Grey was named chief executive officer of Paramount Pictures Corporation in 2005. In his position, Grey was responsible for overseeing all feature film development and production for films distributed by Paramount Pictures Corporation including Paramount Pictures, Paramount Vantage, Paramount Classics, Paramount Insurge, MTV Films and Nickelodeon Movies.[27] He was also responsible for the worldwide business operations for Paramount Pictures International, Paramount Famous Productions, Paramount Home Media Distribution, Paramount Animation, Studio Group and Worldwide Television Distribution.[28]

Among the commercial and critical hit films Paramount produced and/or distributed during Grey's tenure were the Transformers, Paranormal Activity, and Iron Man franchises, Star Trek, How to Train Your Dragon, Shrek the Third, Mission: Impossible III, Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, An Inconvenient Truth, There Will Be Blood, No Country for Old Men, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Babel, Shutter Island, Up in the Air, The Fighter, True Grit, The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn, and Hugo.

During his time as chairman and CEO of Paramount, the studio's films were nominated for dozens of Academy Awards, including 20 in 2011[29] and 18 in 2012.[30]

After arriving at Paramount in 2005, Chairman and CEO Grey was credited with leading a return to fortune at the box office.[31] He oversaw the creation and revitalization of several major franchises, Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, Star Trek, and Paranormal Activity, which was made for $15,000 and generated $192 million at the global box office.[3] Paranormal Activity 2 grossed $177 million worldwide, and the third installment in the franchise collected $205.7 million worldwide in 2011.[32] A fourth installment was released in October 2012. The studio's 2011 results included Transformers: Dark of the Moon, which grossed more than $1.1 billion worldwide, and Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, whose $694 million global box office tally makes it the most successful entry in that franchise.[33][34] Paramount's 2012 slate included The Dictator which earned $179 million on a $65 million budget.[2][35]

During this period, Paramount forged productive relationships with top-tier filmmakers and talent including J. J. Abrams, Michael Bay and Martin Scorsese.[36]

In 2011, based on the success of Rango, the studio's first original, computer-animated release, Grey oversaw the launch of a new animation division, Paramount Animation.[37]

The 2010 Paramount slate achieved much success with Shutter Island and True Grit reaching the biggest box office totals in the storied careers of Martin Scorsese and the Coen brothers, respectively. In addition, during Grey's tenure, Paramount launched its own worldwide releasing arm, Paramount Pictures International, and has released acclaimed films such as An Inconvenient Truth, Up in the Air and There Will Be Blood. The success of Paranormal Activity also led to the creation of a low-budget releasing label Insurge Pictures, which released Justin Bieber: Never Say Never, which collected nearly $100 million in worldwide box office revenue.[38]

Grey was ousted from Paramount Pictures shortly before his death, a result of a power struggle between his backers and the family of majority owner Sumner Redstone, along with a series of flops that cost the studio $450 million in losses.[39]

Death

Grey died on May 14, 2017 from cancer at his Holmby Hills home in Los Angeles, California.[40] He was 59.[41][42] He is buried at Hillside Cemetery in Culver City, California.

Philanthropy

Grey received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from SUNY during a visit to Buffalo and UB in 2003.[43] Grey's Board appointments included:

UCLA's Executive Board for the Medical Sciences[44]

USC School of Cinema-Television Board of Councilors[45]

Board of Directors for Project A.L.S.[46]

NYU's Tisch School of the Arts[47]

Los Angeles County Museum of Art[48]

Filmography

All films, he was producer unless otherwise noted.

Film

Year Film Notes

1990 Opportunity Knocks Executive producer

1996 Happy Gilmore Executive producer

The Cable Guy Executive producer

Bulletproof Executive producer

1998 The Replacement Killers

The Wedding Singer Executive producer

Dirty Work Executive producer

2000 What Planet Are You From? Executive producer

Screwed Executive producer

Scary Movie Executive producer

2002 City by the Sea

2003 View from the Top

2005 Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

2006 The Departed

Running with Scissors

2007 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford Executive producer

Final film as a producer

As writer

Year Film Notes

1981 The Burning Original story

Miscellaneous crew

Year Film Notes

1981 The Burning Production consultant

Thanks

Year Film Notes

2006 Babel The director wishes to thank

2008 Taste of Flesh Direct-to-video - Very special thanks

2010 I'm Still Here Special thanks

TBA The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time Special thanks

Television

Year Title Notes

1984 Garry Shandling: Alone in Vegas Television special

1986 The Garry Shandling Show: 25th Anniversary Special Television special - Executive producer

1988 Mr. Miller Goes to Washington Starring Dennis Miller Television special - Executive producer

The Boys Executive producer

1989 The 13th Annual Young Comedians Special Television special - Executive producer

1990 Normal Life Executive producer

Don't Try This at Home! Television film - Executive producer

Dennis Miller: Black and White Television special - Executive producer

Bob Saget: In the Dream State Television special - Executive producer

1986−90 It's Garry Shandling's Show Executive producer

1991 Good Sports Executive producer

1992 The Please Watch the Jon Lovitz Special Television special - Executive producer

The 15th Annual Young Comedians Special Television special - Executive producer

1993 Live from Washington D.C.: They Shoot HBO Specials, Don't They? Television special - Executive producer

1995 Dana Carvey: Critics' Choice Television special - Executive producer

1996 For Hope Television film - Executive producer

Mr. Show with Bob and David: Fantastic Newness Television short - Executive producer

1995−97 The Jeff Foxworthy Show Executive producer

Mr. Show with Bob and David Executive producer

The Naked Truth Executive producer

1997 C-16: FBI Executive producer

1997−98 Alright Already Executive producer

1992−98 The Larry Sanders Show Executive producer

1998 Mr. Show and the Incredible, Fantastical News Report Television short - Executive producer

Applewood 911 Television film - Executive producer

1995−99 NewsRadio Executive producer

2000 Sammy Executive producer

1996−2002 The Steve Harvey Show Executive producer

Politically Incorrect Executive producer

2002 In Memoriam: New York City Documentary - Executive producer

Father Lefty Television film - Executive producer

2001−02 Pasadena Executive producer

2003 My Big Fat Greek Life Executive producer

Married to the Kellys Executive producer

The Lyon's Den Executive producer

Titletown Television film - Executive producer

1997−2003 Just Shoot Me! Executive producer

2004 Three Sisters: Searching for a Cure Documentary - Executive producer

2005 Jake in Progress Executive producer

East of Normal, West of Weird Television film - Executive producer

2004−06 Cracking Up Executive producer

1999−2007 The Sopranos Executive producer

2006−19 Real Time with Bill Maher Executive producer

Awards

Award Year Work Category Ref.

Emmy 2004 The Sopranos Outstanding Drama Series [49]

Emmy 2007 The Sopranos Outstanding Drama Series [49]

Peabody 1993 The Larry Sanders Show [50]

Peabody 1998 The Larry Sanders Show [51]

Peabody 1999 The Sopranos [52]

Peabody 2000 The Sopranos [53]

PGA 2000 The Sopranos [54]

PGA 2005 The Sopranos Norman Felton Producer of the Year – Episodic [54]

PGA 2008 The Sopranos Norman Felton Producer of the Year – Episodic [54]

References

1. Cieply, Michael (2009-01-08). "New York Times, Jan 2009". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

2. Finke, Nikki (2012-01-02). "Paramount Topples Warner Bros For #1 In 2011 Market Share With Record $5.17B Worldwide, Jan 2012". Deadline.com. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

3. Cieply, Michael (2009-12-13). "New York Times, Dec 2009". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

4. Biskind, Peter (2012-06-11). "Vanity Fair, July 2012". VanityFair.com. Retrieved 2012-07-19.

5. Joel Stein (December 19, 2008). "Who runs Hollywood? C'mon". LA Times. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

6. Jewish Journal: "The Heroes of Jewish Comedy" by Tom Teicholz July 3, 2003

7. Brook, Vincent. From Shtetl to Stardom: Jews and Hollywood: Chapter 1: Still an Empire of Their Own: How Jews Remain Atop a Reinvented Hollywood. Purdue University Press. p. 15.

8. O'Shei, Tim (15 May 2017). "Brad Grey, UB grad-turned-Hollywood mogul, dies at 59". The Buffalo News. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

9. "Yahoo! Movies". Movies.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

10. "WMA.com" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-05-08.

11. "New York Times July 3, 1999". Nytimes.com. 1999-07-03. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

12. Bates, James (1999-07-03). "LA Times July 3, 1999". Articles.latimes.com. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

13. Abramowitz, Rachel (2008-03-17). "LA Times March 17, 2008". Articles.latimes.com. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

14. Halbfinger, David M. (2008-03-14). "New York Times March, 2008". Los Angeles (Calif): Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

15. "Huffington Post March, 2008". Huffingtonpost.com. 2008-03-18. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

16. Garrett, Diane (2008-03-17). "Variety Mar. 17, 2008". Variety.com. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

17. "Hollywood Harassment: I Was Fired from a Hit Show and Intimidated By Lawyers (Guest Column)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

18. Shprintz, Janet (2002-05-28). "Judge throws out Zenga's 'Scary' suit". Variety. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

19. "Bo Zenga". IMDb. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

20. "Scary Movie (2000) - Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

21. Halbfinger, David M.; Weiner, Allison Hope (2006-03-24). "Evidence of Wiretaps Used in Suit". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

22. Hazelton, John (2005-06-23). "Screen Daily". Screen Daily. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

23. "Brad Grey Escapes Liability in Anthony Pellicano Matter". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

24. Finke, Nikki (2008-03-20). "Brad Grey's Pellicano Testimony: "Boring"". Deadline. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

25. B, Tom (2017-05-15). "Boot Hill: RIP Brad Grey". Boot Hill. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

26. "Comedy Writer Reveals Lurid Details of Harassment on Set — and Why It Cost Her a Job (Guest Column)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

27. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-11. Retrieved 2012-07-17., Paramount Picture

28. "Paramount Corporate". Paramount.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

29. "Reuters Jan 25th, 2011". 2011-01-25.

30. Finke, Nikki (2012-01-24). "OSCARS: Nominations By Studio – Sony 21, Paramount 18, Weinstein 16, Disney 13, Fox 10, Universal 7, Warner Bros 5, Roadside Attractions 4". Deadline.com. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

31. Lauria, Peter (2010-02-12). "New York Post, February 2010". Nypost.com.com. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

32. "Box Office Mojo: Paranormal Activity 3". BoxOfficeMojo.com. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

33. Subers, Ray (2012-02-07). "Around-the-World Roundup: 'M:I-4' Passes $600 Million Worldwide". BoxOfficeMojo.com. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

34. "Transformers: Dark of the Moon". BoxOfficeMojo.com. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

35. "The Dictator". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

36. "New York Times, November 8, 2006". Nytimes.com.com. 2006-11-08. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

37. Miller, Daniel (2011-10-10). "David Stainton Tapped to Run Paramount Animation". HollywoodReporter.com. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

38. "Box Office Mojo".

39. Lang, Brent; Oldham, Stuart (15 May 2017). "Former Paramount CEO Brad Grey Dies at 59". Variety. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

40. Smith, Harrison (May 15, 2017). "Brad Grey, 'Sopranos' producer who led Paramount studios, dies at 59". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

41. Kilday, Gregg (May 15, 2017). "Brad Grey, Former Head of Paramount Pictures, Dies at 59". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

42. Faughnder, Ryan; Miller, Daniel (May 15, 2017). "Brad Grey, the old-school mogul who ran Paramount Pictures, dies at 59". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

43. "Univ Buffalo Archives". Buffalo.edu. 2003-04-03. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

44. "UCLA Health". UCLA Health. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

45. "USC Cinema". Cinema.usc.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-08-26. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

46. "Project A.L.S." Archived from the original on 2007-10-11.

47. "Tisch NYU, 2004". Tisch.nyu.edu. 2004-11-09. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2011-05-08.

48. Pener, Degen (2013-06-19). "Paramount Pictures' Brad Grey Joins LACMA as Trustee (Exclusive)". HollywoodReporter.com. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

49. "Brad Grey". Emmys. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

50. "The Larry Sanders Show (HBO): Winner 1993". Peabody. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

51. "The Larry Sanders Show: Flip (HBO): Winner 1998". Peabody. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

52. "The Sopranos (HBO): Winner 1999". Peabody. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

53. "The Sopranos (HBO): Winner 2000". Peabody. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

54. "PGA Award Winners 1990-2010". Producers Guild of America. Retrieved May 15, 2017.