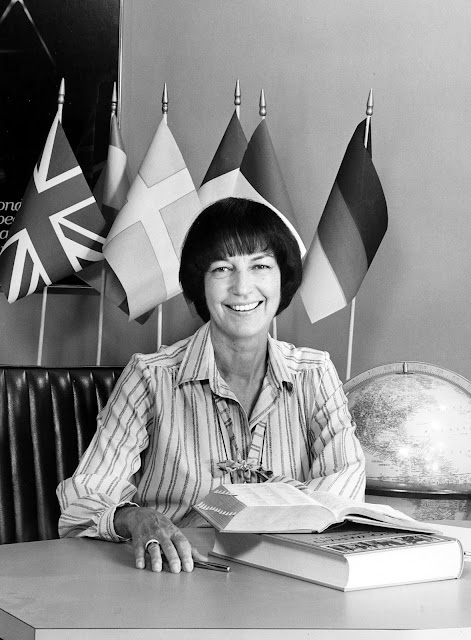

Fay Kanin (née Mitchell; May 9, 1917 – March 27, 2013) was an American screenwriter, playwright and producer. Kanin was President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences from 1979 to 1983.

Biography

Born Fay Mitchell in New York City to David and Bessie (née Kaiser) Mitchell, she was raised in Elmira, New York, where she won the New York State Spelling Championship at twelve and was presented with a silver cup by then Governor Franklin Roosevelt. She was encouraged to write for money by supplying small items to the Elmira Star Gazette.[1]

In high school she wrote and produced a children's radio show; then on full scholarship, she attended the private, all-female Elmira College where she divided her studies between writing and acting as well as editing the yearbook. Fay's mother took her daughter to visit her grandmother in the Bronx, and it was there that she became devoted to the theater when she saw a matinée of Idiot's Delight starring Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne.[2]

Hollywood

Kanin longed to move to Los Angeles to get into pictures and her parents indulged her. Her father moved to California first to secure a job, then she and her mother packed everything and followed by train.[3] Kanin spent her senior year at the University of Southern California where she became active in college radio. After graduating with a bachelor's degree, she wangled an interview with Sam Marx who thought she was much too young to hire; but her next interview was with story editor Bob Sparks at RKO who sent her to producer Al Lewis, who then hired her as a story editor at $75 a week.[2] RKO released Lewis, but Sparks kept Fay on as scriptreader to write one-page summaries for $25 a week. Kanin proceeded to teach herself everything she could about the movie industry at RKO's expense. During the lunch hour, she talked to anyone she happened to find – whether they were art directors, editors, or cinematographers.[3]

Michael Kanin

There was a small theater at the studio where contract players put on plays. While Kanin was acting in Irwin Shaw's Bury the Dead, she came to the attention of Michael Kanin, who had just been hired as a writer in the B unit. Michael was trained as an artist and had turned to commercial art and painting scenery for burlesque houses to help support his parents during the Depression. They were introduced by a mutual friend, and Michael practically asked Kanin to marry him right then and there, but it took her a little while to come around to the idea.[2]

The Kanins rented a house in Malibu for their honeymoon, and after buying an A. J. Liebling New Yorker short story about a boarding house for boxers, they spent the next six months writing the adaptation, Sunday Punch (1942). They knew they were on the track to a partnership when MGM bought the screenplay.

"We would make a story outline together with rather detailed descriptions of the scenes. Then we divided up the writing, each taking the scenes we felt strongly about. Then one or the other of us would put it all together into a single draft. We did find a common voice, though we had different strengths. As an artist, Michael brought a great visual sense to the process. I was a people person who loved the characters and the dialogue. Through the collaboration, we learned a lot from each other and about each other. But the time came when I felt as if we were together 48 hours a day. Writing with someone else always requires some degree of compromise, as does marriage. When it came down to the question of which would survive, the marriage or the writing partnership, it was a pretty easy decision. But I remember that it was a challenge convincing the powers that be that we had been successful writers individually and would be again. We were hyphenated in people's minds: Fay-and-Michael Kanin. To again become Fay Kanin and Michael Kanin took some doing."[2]

Michael took a job working with Ring Lardner Jr. to work on the Tracy / Hepburn project Woman of the Year (1942), based on an original story by his brother Garson Kanin. Fay and Michael Kanin wrote a play, Goodbye My Fancy, about a female congressional representative renewing past loves. The play was a Broadway smash and starred Madeleine Carroll, Conrad Nagel, and Shirley Booth,[2] and was eventually filmed by Vincent Sherman in 1951 with Joan Crawford and Robert Young.

During World War II, Kanin came up with an idea to promote women's participation in the war effort, and presented the idea for A Woman's Angle radio show to the heads of NBC Radio for which Kanin would write the scripts and do the network commentary.[3] Along those lines, she contributed to the story Blondie For Victory, one of the low-budget series based on the popular comic strip, where Blondie organizes Housewives of America to perform homefront wartime duties much to the dismay of Dagwood. Kanin even made an appearance as an actor in A Double Life (1947), co-written by her brother-in-law Garson Kanin and his wife, actress Ruth Gordon.[2]

Teacher's Pet

The Kanins wrote My Pal Gus (1952) in which Richard Widmark becomes a good father and falls in love with Joanne Dru, the Elizabeth Taylor film Rhapsody (1954) and The Opposite Sex (1956), a musical remake of The Women. But it was the Oscar-nominated script for Teacher's Pet (1958) for which they are best remembered, a film about a self-made newspaper editor Clark Gable who has a love-hate relationship with journalism teacher Doris Day. The film almost did not get made since the Kanins were not under any studio contract, and having shopped the script around without attracting any interest, it was only after a rewrite inspired by Garson Kanin's Born Yesterday that producer Bill Perlberg and director George Seaton purchased it.[2]

Blacklist

It was while the couple were on holiday in Europe that the Kanins learned they had been blacklisted by the HUAC.

"What they had against us was that I had taken classes at the Actors Lab in Hollywood where some of the teachers were from the Group Theater and therefore suspect, and we had been members of the Hollywood Writers Mobilization, an organization in support of World War II to which almost all of Hollywood's writers belonged. It was ridiculous, but it was very real, and there was nothing we could do about it. We took a larger mortgage on the house and started writing a play, but we didn't work in films for almost two years."

They were unable to find work again until director Charles Vidor insisted that MGM hire the couple for Rhapsody in 1953.[2]

Rashomon

In 1959 the couple adapted Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon for the Broadway play of the same name; with a further adaptation for the screen, in Martin Ritts The Outrage.

Television

In the early 1970s, Kanin began solo writing in earnest with Heat of Anger, about a strong, older woman lawyer played by Susan Hayward, and a younger male lawyer. At first Kanin was put off by the lack of an immediate reaction from an audience, but once she realized that more people had seen it in one night than would have ever seen it in theaters if it played for a year, she was hooked and wrote five more films for television.[2]

Tell Me Where it Hurts started from a small newspaper article about a group of women in Queens who got together to just talk. The film starred Maureen Stapleton and won two Emmys.

The following year, she wrote and co-produced Hustling based on Gail Sheehy's non-fiction book. The film was about a prostitute recounting her life to a reporter, and starred Jill Clayburgh and Lee Remick, respectively. For weeks, Kanin interviewed working girls at the Midtown North police station, and after the film aired, she received letters complimenting her on how fairly she had treated them.[2]

The television movie Friendly Fire was seen by an estimated sixty million people in 1979. Written and co-produced by Kanin, it starred Carol Burnett as a mother who challenges the military's "official story" of how her son died in Vietnam. The non-fiction book by C. D. B. Bryan was about the Mullen family and their discovery that their son had been accidentally killed by American troops. Kanin spent five months secluded with Bryan's research tapes adapting the book, and Friendly Fire won the Emmy for Best Outstanding Drama that year.[4]

In 1978, Kanin and the producer of Hustling, Lillian Gallo, partnered to form a joint production company, becoming one of the first female production teams in Hollywood.[5] Together, their company produced Fun and Games for Valerie Harper, a tale of sexual harassment and gender discrimination in the workplace.[6] For Norman Lear, Kanin wrote Heartsounds, which starred Mary Tyler Moore and James Garner as a couple coping with heart disease.

Grind

In 1975, Universal Studio producers asked Kanin for a screenplay about a bi-racial burlesque theater in 1933 Chicago. Nothing came of it, but in 1985 Kanin adapted her unproduced screenplay for the stage.[7] The result was Grind.[8] Directed by Hal Prince with choreography by Lester Wilson, the cast included Ben Vereen as a song-and-dance man, Stubby Kaye as a slapstick comic, and Leilani Jones as a stripper named Satin. The production was a disaster; the show lost its entire $4.75 million investment, and Prince and three other members of the creative team were suspended by the Dramatists Guild of America for signing a "substandard" contract.

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Kanin was elected president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1979, and served four terms until 1983.[9] She was its second female president, following in the footsteps of earlier president Bette Davis, who left after only one month. She has also served as the president of the Screen Branch of the Writers Guild of America and as Chair of the National Film Preservation Board of the Library of Congress, an officer of the Writers Guild Foundation, a member of the Board of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and a member of the Board of Directors of the American Film Institute.

Fay Kanin was the vice president of the Academy's 1999–2000 Board of Trustees, and a member of the steering committee of the Caucus for Producers, Writers and Directors, which formed in 1974, and of the National Film Preservation Board in Washington, D.C.[10] She served on the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Board of Governors from 2007–08.

Death

Fay Kanin died on March 27, 2013. She is interred in the Beth Olam Mausoleum at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. Her husband, Michael Kanin, who died on March 12, 1993, and their son, Joel Kanin, who died on November 14, 1958, are also interred in the same mausoleum.

Filmography

Sunday Punch (1942, screenplay, story)

Blondie for Victory (1942, story)

Goodbye, My Fancy (1951, play)

My Pal Gus (1952, original screenplay)

Rhapsody (1954, screenplay)

The Opposite Sex (1956, screenplay)

Teacher's Pet (1958, screenplay)

Rashomon (1959, adaptation)

The Right Approach (1961, screenplay)

Play of the Week: Rashomon (1961, teleplay adaptation)

Congiura dei dieci, La (1962, screenplay)

The Outrage (1964, adaptation)

Heat of Anger (1972, teleplay)

Tell Me Where It Hurts (1974, teleplay)

Hustling (1975, teleplay, associate producer)

Friendly Fire (1979, teleplay, co-producer)

Fun and Games (1980, TV producer)

Heartsounds (1984, teleplay, producer)

Stage Productions

Goodbye, My Fancy (1947)

His and Hers (1954) w/ Michael Kanin

Rashomon (1959) w/ Michael Kanin

The Gay Life (1961) w/ Michael Kanin (later retitled as The High Life)

Grind (1985)

Awards

Year Group Award Result Recipient

1959 Academy Award Best Writing, Story and Screenplay – Written Directly for the Screen Nominated Teacher's Pet w/ Michael Kanin

1959 WGA Award (Screen) Best Written American Comedy Nominated Teacher's Pet w/ Michael Kanin

1972 American Bar Association The Gavel Award for Best Movie of 1972 devoted to the Law Heat of Anger

1974 EMMY Best Writing in Drama – Original Teleplay Won Tell Me Where It Hurts

1974 EMMY Writer of the Year – Special Won Tell Me Where It Hurts

1975 Writers Guild of America Valentine Davies Award

1976 Edgar Allan Poe Awards Edgar Best Television Feature or Miniseries Nominated Hustling

1976 EMMY Outstanding Writing in a Special Program – Drama or Comedy – Original Teleplay Nominated Hustling

1978 EMMY Outstanding Writing in a Limited Series or a Special Nominated Friendly Fire

1978 EMMY Outstanding Drama/Comedy Special Won Friendly Fire

1979 Humanitas Prize 90 Minute Category Nominated Friendly Fire

1980 Writers Guild of America Morgan Cox Award

1980 Women in Film Crystal Awards Crystal Award Recipient for outstanding women who, through their endurance and the excellence of their work, have helped to expand the role of women within the entertainment industry.[11]

1985 EMMY Outstanding Drama/Comedy Special Nominated Heartsounds

1985 TONY Book (Musical) Nominated Grind

1993 American Society of Cinematographers Board of the Governors Award

1993 PGA Awards PGA Hall of Fame – Television Programs Won Friendly Fire

2003 Humanitas Prize Kieser Award

2005 Writers Guild of America Edmund J. North Award

Non-profit organization positions

President of Academy of Motion Pictures, Arts and Sciences 1979-1983

References

Notes

1. Lefcourt. 2000. 2. Beauchamp.2001.

3. Acker. 1991.

4. Gregory 2001.

5. "Lillian Gallo, Pioneering TV Producer, Dies at 84". The Hollywood Reporter. 2012-06-18. Retrieved 2012-06-26.

6. Slide. 1991.

7. Jones. 2004.

8. Robinson. 1989.

9. Levy. 2003.

10. "Jewish Women's Archive".

11. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 30, 2011.

Bibliography

Acker, Ally (1991). Reel women: pioneers of the cinema 1896 to the present. London: Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-6960-9.

Beauchamp, Cari (September 2001). "Woman of the Years: An interview with Fay Kanin". Written by (the magazine of the Writers Guild West).

Gregory, Mollie (2002). Women who run the show: how a brilliant and creative new generation of women stormed Hollywood. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-30182-0.

Jones, John Philip (2004). Our Musicals, Ourselves: A Social History of the American Musical Theater. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. ISBN 0-87451-904-7.

Lefcourt, Peter ed. (2000). The First Time I Got Paid For It : Writers' Tales From The Hollywood Trenches. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-58648-013-8.

Levy, Emanuel (2003). All about Oscar: the history and politics of the Academy Awards. London: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-1452-4.

Robinson, Alice M.; Roberts, Vera Mowry (1989). Notable women in the American theatre: a biographical dictionary. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-27217-4.

Slide, Anthony (1991). The Television industry: a historical dictionary. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-25634-9.

No comments:

Post a Comment