Evelyn Nesbit (December 25, 1884 – January 17, 1967) was an American artists' model and chorus girl, noted for her entanglement in the murder of her ex-lover, architect Stanford White, by her first husband, Harry Kendall Thaw.

Early life

She was born Florence Evelyn Nesbit on December 25, 1884 in Tarentum, a small village near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She was of Scots-Irish ancestry. As a child, Florence Evelyn was strikingly beautiful, but quiet and somewhat shy.[1] She had a younger brother, Howard.

The Nesbit family moved to Pittsburgh around 1893, when Evelyn was still a schoolgirl. Her father, a struggling lawyer named Winfield Scott Nesbit, died that year, leaving behind substantial debts; his wife and two children were nearly destitute. For years Evelyn and her mother and younger brother lived in near-poverty, but by the time she reached adolescence her startling beauty came to the attention of several local artists, including John Storm, and she was able to find employment as an artists' model.

Modeling career

In 1901, when Nesbit was sixteen, she and her mother moved into a tiny room at 249 W. 22nd Street in New York City. Her mother had difficulty in finding work and after several weeks, Evelyn persuaded her to let her model again. Using a letter of introduction from a Philadelphia artist, Evelyn met and posed for James Carroll Beckwith, who introduced her to other New York artists. Soon she began modeling for artists Frederick S. Church, Herbert Morgan, Gertrude Käsebier, Carl Blenner and photographer Rudolf Eickemeyer, Jr.

Eventually, Evelyn became one of the most in-demand artists' models in New York. She was seductively beautiful with long, wavy red hair and a slender, shapely figure. Charles Dana Gibson, one of the most popular artists in the country at the time, rendered a pen-and-ink profile of Evelyn with her red hair arranged in the form of a question mark. The work, titled "The Eternal Question"[1], remains one of Gibson's best known works and Evelyn entered the ranks of the famous turn-of-the-century "Gibson Girls."

Photographic fashion modeling, which was becoming more popular in daily newspapers, proved to be even more lucrative for Evelyn. Photographer Joel Feder would pay her $5 for a half-day shoot or $10 for a full day shoot (about $200 per day in 2006 dollars). Evelyn soon made more than enough money to support her family.

Relationships

Stanford White

As a chorus girl on Broadway in 1901, Nesbit was introduced to acclaimed architect Stanford White by Edna Goodrich,[2] who was a member along with Nesbit in the company performing Florodora at the Casino Theatre. White—a notorious womanizer known as "Stanny" by his close friends and relatives—was then 47 years of age to her 16.

White had a loft apartment on West Twenty-fourth Street above FAO Schwarz with its walkup doorway situated next to the toy store's back delivery entrance. In her memoir Prodigal Days, Nesbit described her introduction to White at the apartment, decorated with heavy red velvet curtains and fine paintings, where White and a man named Reginald Ronalds poured her a glass of champagne and led her upstairs to a studio outfitted with a red velvet swing.[3] While nothing untoward occurred on that first visit, the swing would later become notorious as accounts of its use were aired in the course of a murder trial, and some sources incorrectly state the activities that formed the basis for the 1955 film The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing took place at the "Tower Room" at the old Madison Square Garden, where White kept an office.[4] Nesbit states specifically that the swing and its related activities took place at the apartment on West Twenty-fourth Street.[3] Although White reportedly derived sexual pleasure by pushing young women in the swing, naked or nearly so, as Nesbit later testified in court, she claimed her own later nude escapades with White were simply for his "aesthetic" delight.

Stanford White had endeared himself to Nesbit's mother by making arrangements for her son to be admitted to the Chester Military Academy near Philadelphia, and she placed so much trust in the architect that when she arranged an out-of-town trip, Stanford White and Evelyn Nesbit saw her off at the train station, where she left her daughter in his care.[5]

Several nights after her mother left for Pittsburgh, Nesbit was summoned to the apartment by White, where the two shared dinner and several glasses of champagne before she was given a tour that ended in the "Mirror Room." On the same upper floor as the studio featuring the velvet swing, the ten-by-ten room held a green velvet-covered couch and walls and ceilings covered with mirrors. Later, after more champagne, the two returned downstairs and Nesbit tried on a yellow satin kimono before she "passed out." She recounted that she awoke in bed, nearly naked with White lying beside her, and that she "entered that room a virgin," but did not come out as one.[6]

Later, Nesbit related this story to millionaire Harry Thaw after he repeatedly hounded her to know why she refused to marry him. She later did, but at the end of her life, Nesbit claimed that the charismatic "Stanny" was the only man she had ever loved.

John Barrymore

As White moved on to other young, virginal women, Nesbit was courted by the young John Barrymore, beginning in 1901. The two met when Barrymore caught a performance of The Florodora Girls and sent flowers backstage. Barrymore, who was from a well known theatrical family, was then 19 and seeking a career in cartooning. He was considered too poor by her mother to be a suitable match for the 17-year-old Nesbit. Her mother and White were enraged when they found out about the relationship. However, Nesbit was finally smitten with someone her own age and often returned to Barrymore's apartment after hours. White, still a strong influence in her life, arranged to send her away to a boarding school in Wayne, New Jersey (run by the mother of film director Cecil B. DeMille) in part to extricate her from John Barrymore. Barrymore in the meantime proposed marriage to Nesbit, in the presence of Mrs Nesbit and White, but Evelyn turned down his offer.

Harry Kendall Thaw, husband of Evelyn Nesbit

Stanford White and John Barrymore were subsequently supplanted in Nesbit's life by Harry Kendall Thaw (1871–1947) of Pittsburgh, the son of a coal and railroad baron. Prior to her relationship with Thaw, Nesbit dated a well known polo player named James "Monty" Waterbury (1875–1920) and the young magazine publisher Robert J. Collier. Thaw was extremely possessive of Nesbit (he reportedly carried a pistol), and obsessive about the details of her relationship with White (whom he referred to as "The Beast"). Thaw was a cocaine addict and allegedly a sadist who subjected women—including Nesbit—and the occasional adolescent boy to severe whippings. However, following a trip to Europe, Nesbit finally accepted Thaw's repeated marriage proposal. They were wed on April 4, 1905, when Nesbit was twenty.

Nesbit had one child, Russell William Thaw (above with Evelyn), who was born in Berlin on October 25, 1910 (he died in 1984 at Santa Barbara, California). A noted pilot in World War II, as a child he appeared in Hollywood films with his mother. The identity of his father, however, remains in doubt. While Thaw swore he was not the child's father (he was conceived and born during Thaw's confinement), Nesbit always insisted that he was.

Murder of Stanford White

On June 25, 1906, Nesbit and Thaw saw White at the restaurant Café Martin and ran into him again later that night in the audience of the Madison Square Garden's roof theatre at a performance of Mam'zelle Champagne, written by Edgar Allan Woolf. During the song "I Could Love A Million Girls," Thaw fired three shots at close range into White's face, killing him instantly and reportedly exclaiming, "You'll never go out with that woman again.[7] In his book The Murder of Stanford White, Gerald Langford quoted Thaw as saying "You ruined my life," or "You ruined my wife," and the New York Times account the following day stated "Another witness said the word was "wife" instead of "life"" in response to the arresting officer's report otherwise.[7]

Harry Thaw was tried twice for the murder of Stanford White. At the first, the jury was deadlocked; at the second (in which Nesbit testified in his behalf), Thaw pleaded temporary insanity. Thaw's mother (usually referred to as "Mother Thaw") promised Nesbit that if she would testify that White had raped her and that Thaw had only tried to avenge her honor, she would receive a quiet divorce and a one million dollar divorce settlement. Nesbit got the divorce, but never saw a cent of the million. Immediately following Thaw's acquittal, she was cut off financially by Thaw's mother.

Thaw was incarcerated at the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Beacon, New York, but enjoyed almost total freedom. Still, he tried to escape a couple of times to Canada. In 1913, he strolled out of the asylum and was driven over the Canadian border into Sherbrooke, Quebec. He was extradited back to the U.S., but in 1915 was released from custody after being judged sane.

Later years

In the years following the second trial, Nesbit's career as a vaudeville performer, silent film actress and cafe manager was only modestly successful, her life marred by suicide attempts. In 1914, she appeared in Threads of Destiny produced at the Betzwood studios of film producer Siegmund Lubin.[8] In 1916, after her divorce from Thaw, she married her dancing partner, Jack Clifford (1880–1956, born Virgil James Montani). He left her in 1918, and she divorced him in 1933.

In 1926 Nesbit gave an interview to the New York Times, stating that she and Thaw had reconciled, but nothing came of the renewed relationship. Nesbit published two memoirs, The Story Of My Life (1914), and Prodigal Days (1934).

She lived quietly for several years in Northfield, New Jersey. She overcame suicide attempts, alcoholism, and an addiction to morphine, and in her later years taught classes in ceramics. She was a technical adviser on the 1955 movie The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing.

Death

She died in a nursing home in Santa Monica, California on January 17, 1967, at the age of 82.[9][10] Nesbit was buried in Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California.

In popular culture

Charles Dana Gibson reportedly used Nesbit as the inspiration for his illustrations of the "Gibson Girl."

The author Lucy Maud Montgomery used a photograph of Nesbit—from the Metropolitan Magazine and pasted to the wall in her bedroom —as the model for the heroine of her book Anne of Green Gables (1908).[11]

In Dalton Trumbo's Johnny Got His Gun, in chapter 14, the character "Bonnie" asks the protagonist if she looks like Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, because "all her husbands said she looked just like [her]."

The 2007 novel Laura Warholic; or, The Sexual Intellectual by Alexander Theroux features a photograph of Nesbit for its cover.

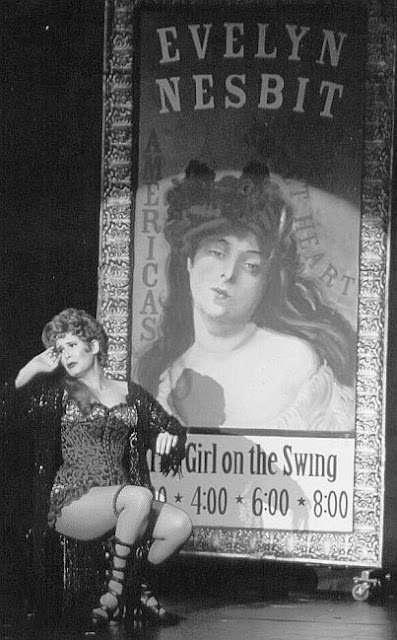

Featured in Ragtime (musical), one of the subplots includes the story of Stanford White's murder, and how it led to more fame and publicity for Evelyn. She sings in the songs "Crime of the Century" and "Atlantic City."

Non-fiction accounts

The Architect of Desire – Suzannah Lessard (White's great-granddaughter)

Glamorous Sinners – Frederick L. Collins

Evelyn Nesbit and Stanford White: Love and Death in the Gilded Age – Michael Mooney

Looking for Anne of Green Gables – Irene Gammel

The Murder of Stanford White – Gerald Langford

The Traitor – Harry K. Thaw

The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing – Charles Samuels

The Story of my Life – Evelyn Nesbit Thaw – 1914

Prodigal Days – Evelyn Nesbit Thaw – 1934

American Eve: Evelyn Nesbit, Stanford White The Birth of the 'It' Girl, and the 'Crime of the Century' – Paula Uruburu – 2008

Fictional accounts

The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing (1955 movie)

The 1975 historical fiction novel Ragtime by E. L. Doctorow was adapted into the two works below:

The film Ragtime.

The musical Ragtime. (in the song "Crime of the Century" and later in the show during the song "Atlantic City")

Dementia Americana - A long narrative poem by Keith Maillard (1994)

My Sweetheart's the Man in the Moon – play by Don Nigro

La fille coupée en deux (A Girl Cut in Two) – film by Claude Chabrol (2007)

Boardwalk Empire – HBO Television Series - Character of Gillian loosely based on Evelyn Nesbit (2010)

References

1.^ EvelynNesbit.com

2.^ Prodigal Days; Evelyn Nesbit, Julian Messner Publishers, New York, 1934, page 3.

3.^ Prodigal Days; Evelyn Nesbit, Julian Messner Publishers, New York, 1934, page 27.

4.^ Dworin, Caroline H. (2007-11-04). "The Girl, the Swing and a Row House in Ruins". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/04/nyregion/thecity/04swin.html. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

5.^ Prodigal Days; Evelyn Nesbit, Julian Messner Publishers, New York, 1934, page 37.

6.^ Prodigal Days; Evelyn Nesbit, Julian Messner Publishers, New York, 1934, page 41.

7.^ "Thaw Murders Stanford White New York Times; June 26, 1906; page 1.

8.^ Prodigal Days; Evelyn Nesbit, Julian Messner Publishers, New York, 1934, page 276.

9.^ "Mrs. Thaw Dies; Early Trial Figure". Los Angeles Times News Service. January 18, 1967. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=M5wRAAAAIBAJ&sjid=vOgDAAAAIBAJ&pg=6092,853626&dq=russell+thaw+dies&hl=en. Retrieved 2010-10-09. "Mrs. Thaw, died Tuesday in a convalescent home here. ... After the murder trial she toured Europe with a dancing troupe where a son, Russell Thaw, was born. ..."

10.^ "Evelyn Nesbit, 82, Dies In California; Evelyn Nesbit of '06 Thaw Case Dies". Associated press in the New York Times. January 18, 1967. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40B10F93B58117B93CBA8178AD85F438685F9. Retrieved 2010-10-09. "Evelyn Nesbit, the last surviving principal in the sensational Harry K. Thaw-Stanford White murder case of 60 years ago, died in a convalescent home here yesterday, where she had been a patient, for more than a year. She was 82 years old."

11.^ Irene Gammel, Looking for Anne of Green Gables: The Story of L.M. Montgomery and her Literary Classic (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2009).

Further reading

Prodigal Days: The Untold Story of Evelyn Nesbit, ISBN 978-1-4116-3709-2 also ISBN 1-4116-3709-7

She was beautiful. I’d love to go back in time and make her life better than it was.

ReplyDelete